“The function of art is to do more than tell it like it is – it’s to imagine what is possible.” (hooks, 281) This article discusses artistic occupations of space as a response to violence globally.

On December 16, 2012 in the capital city of the Indian subcontinent, a woman was gang raped, tortured, and inflicted with such bodily harm that she died two weeks later. On the night of the Delhi gang rape case of 2012, Jyoti and her friend Awindra watched a film, after which they attempted to travel home using public transportation in the city. They caught an off duty bus that had been high jacked by a group of men, unaware of the gruesome events that would follow.The case caused massive public protests in Delhi and throughout the Indian subcontinent. Days before the anniversary of the 2012 Delhi gang rape case, the Supreme Court of India made the decision to uphold Section 377[1] of the Indian Penal Code, re-criminalizing same sex desire and queer people after the 2009 decision by the Delhi high court to read down these colonial laws.[2]

Philosopher Michel Foucault’s writings have been foundational to understandings of the relationship between gender, sexuality, and space. Foucault defined the time of capitalist modernity, as one of spatial anxiety, illustrated by responses to female and queer bodies. In this article, I discuss occupations of public space throughout the world by those who enact embodied forms of sexual politics using creative tactics.

The body navigating city streets teeming with the bric-a-brac of market stalls, endless streams of traffic, ornately carved temples and mosques, and shiny buildings housing IT hubs, moves to the tempo of an urban India. This is an India of cities, moving at a pace that is as fast and fleeting as chiming ring tones and as patient and timeless as calls to prayer filtering through the urban metropolis, the lingering sound of sacred songs still haunting the city space.

| The Song O Re Piya by Rateh Fateh Ali Khan is featured in the 2007 film Aaja Nachle. The photo depicts a woman who is pictured as if dancing above the urban metropolis, free from the confining ways in which epistemic and material violence often hinders the movement of women in public spaces. |

The movements of female, transgender, and queer bodies in public spaces are often defined by daily street theatres of cruelty, definitive of what Kannabiran terms, “…the violence of normal times…” (Kannabiran, 3). Certain bodies appear in public space as punch lines and punching bags, across borders. In 2010, Slutwalk emerged as a protest movement after a Toronto police officer suggested that women should not “….dress like sluts,” to prevent rape. Slutwalk involved bodies occupying and refashioning the commons:

| Slutwalk Toronto-CTV News. This news clip documents the beginnings of the Slutwalk movement which started in Toronto, Canada when a police officer stated that if women did not want to be subject to sexual assault they should “..not dress like sluts.” Subsequent protests were held globally, politicizing sexuality and freedom of expression in public spaces. |

Similar protests emerged globally such as Besharmi Morcha in Delhi:

| Slutwalk 2011, Delhi-This video documents Besharmi Morcha, a similar Slutwalk movement which began in Delhi in 2011. The protest was held at Jantar Mantar, a popular cite for public enactments of politics in Delhi. |

While the body marked with the sexual anxieties of others causes negative attention, the body can also be used as a creative tool.

In “Vigil,” Rebecca Belmore, an Aboriginal female artist in white settler Canada, uses her body to pay tribute to murdered and missing Indigenous women, some of whom are sex workers who “disappear” from Vancouver’s lower East Side.

| Rebecca Belmore, This video offers segments of Rebecca Belmore’s performance art installation Vigil. In this striking use of artistic technique, Belmore uses her body and the built spaces of white settler Canada to comment on ongoing colonial violence that impacts upon the lives and deaths of Indigenous women. |

As the artist’s website states,

Performing on a street corner in the Downtown East Side, Belmore commemorates the lives of missing and murdered Aboriginal women who have disappeared from the streets of Vancouver. She scrubs the street on hands and knees, lights votive candles, and nails the long red dress is wearing to a telephone pole. As she struggles to free herself, the dress is torn from her body and hangs in tatters from the nails, reminiscent of the tattered lives of women forced onto the streets for their survival in an alien urban environment. Once freed, Belmore, vulnerable and exposed in her underwear, silently reads the names of missing women that she has written on her arms and then yells them out one by one. After drawing a flower between her teeth, stripping it of blossom and leaf, just as the lives of these forgotten and dispossessed women were shredded in the teeth of indifference. Belmore lets each woman know that she is not forgotten: her spirit is evoked and she is given life by the power of naming.(Belmore, 2015)

Belmore pulls a thorny flower through her teeth fearlessly, screaming out the name of each woman lost to ongoing colonial violence. The red dress signifies female sexuality and by wearing this symbol, Belmore draws attention to the violent sexualization of Aboriginal women and Two Spirited people. Belmore struggles to free her body from the poles, telephone poles in a`red light’ district where Totem Poles are lost to colonial history and public feminisms are as scarce as a city street where Billboard models are not worshipped as Goddesses.

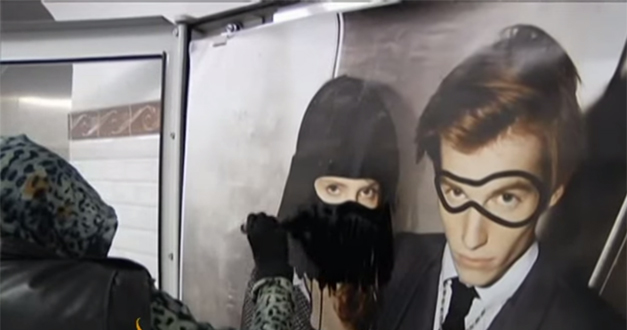

In many cities, the body of the lone artist threatens consumer capitalist complacency. Princess Hjab, a Parisian graffiti artist, “hjabizes” a European public sphere of market driven sexism and Islamophobia:

| Princess Hjab’s “Veiling Art.” This video is a news clip from The Guardian in which the artist Princess Hjab is interviewed regarding their art work, with images of the artist’s ongoing uses of art to reclaim public space in metropolitan France. |

Shopping malls and skyscrapers rise in “world class” cities as a testament to supposed progress. And yet, the threat of sexual violence still follows certain bodies into the streets. The anxiety of becoming a spectacle before a crowd can however be subverted creatively, through novel uses of public space by cultural provocateurs.

While Rebecca Belmore demands that Indigenous women are not forgotten, and Princess Hjab’s graffiti is a welcome sight in a time in which Muslim women are forced out of public space, Delhi’s streets are also stages for political actors:

| Delhi Flash Mob Against Gang Rape 2013—This video documents a flash mob that took place in Delhi, one year after the 2012 Delhi gang rape. Those involved used dance and performance as a means of reclaiming the commons and addressing gender based and sexual violence. |

Beyond borders of nation and skin, many eschew fear to reclaim the commons. There is defiance to the artistic gesture. Theodor Adorno’s writings regarding art, culture, and politics may still to be of relevance today. As Adorno once remarked, “Every work of art is an uncommitted crime.”(Adorno, 111)

[1] Section 377 refers to Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a colonial sodomy law dating back to the 1860’s in the Indian subcontinent. I refer to Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code as “Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code” and “Section 377” as it was often referred to by protesters, activists, and many people whom I spoke with in conducting fieldwork in India.

[2] In 2009, the Delhi high court in India overturned Section 377 of the Indian penal code, a colonial law that criminalizes same sex desire. This happened after a petition was filed by the Naz Foundation in India and after a campaign by the activist group Voices Against 377 in India.

Adorno, Theodor. Minima Moralia: Reflections on a Damaged Life. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1951.

Foucault, Michel and Colin Gordan(Ed.). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977. London: Harvester Press, 1980.

hooks, bell. Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Kannabirān, Kalpana. The Violence of Normal Times. New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2005.

Rebecca Belmore, Artist’s Website. Online Resource. Last Accessed: August 15, 2015.

http://www.rebeccabelmore.com/video/Vigil.html

Tara Atluri

Tara Atluri has a PHD in Sociology. She is a lecturer at the Ontario College of Art and Design University. Between 2012-2014 she held the position of post-doctoral researcher with Oecumene: Citizenship After Orientalism at the Open University in the United Kingdom. During her time as a post- doctoral researcher, she conducted research in India regarding the 2012 Delhi gang rape protests and the 2013 protests that followed the decision by the Supreme Court of India to uphold Section 377 of the Indian penal code, criminalizing diverse enactments of sexuality in the Indian subcontinent. The protests that emerged were remarkable examples of postcolonial sexual politics that inspired the writing of a forthcoming book titled Āzādī: Sexual Politics and Postcolonial Worlds. Tara Atluri will be acting as a Visiting Fellow at Birkbeck College, UK in 2016, where she will work with Dr. Penny Vera-Sanso, Dr. Melissa Butcher and the HERA SINGLE project.

Forthcoming Book: Āzādī: Sexual Politics and Postcolonial Worlds

Tara Atluri will also be participating in the Feminist Art Conference in September, 2015: http://factoronto.org/