A visual essay by Veronika Bereznoj

INTRODUCTION

Image 01: First issue of Vogue Japan, September 1999.

On a regular stroll through a book store, one notices a high variety of women’s fashion magazines. From Elle to Cosmopolitan the eye is spoiled with bright colors and beautiful faces on the issue covers. In the international magazines’ section one finds more “exotic” faces on covers of magazines from other parts of the world, such as China or India. In the case of the Japanese Vogue, however, the Western viewer looks for “exotic” appearances in vain, as Vogue Japan consequently features Western cover models. Despite the lack of a face with at least Asian features, the overall first impression of the magazine is still very Japanese, using almost exclusively Japanese language for the cover headlines. In addition, it is intended to be read from right to left, as the norm for printed media in Japan and therefore clearly designated for a Japanese audience. Why then does the editor choose Caucasian models to represent the magazine? Is this the norm, and if so, how does this appeal to the Japanese reader?[1]

In this essay I pursue these questions through the works of Stuart Hall, Brian Moeran and others on the role of imagining and representing the “other” for the construction of a “self” and the representation of foreigners, or gaijin, as part of a Japanese occidentalism. In addition, through a cover analysis of the Japanese Vogue’s issues of the last 5 years—beginning with the January issue in 2010 and ending with the December issue of 2015—I intend to show how the balance of “Western” and “Japanese” appeal is still maintained by the creators. I argue that despite—and partly because of—the Caucasian faces on the issues’ covers, the Japanese Vogue caters strongly to its local readers and has adapted more to the needs of a Japanese readership than a first impression might suggest. Due to the limited space, however, it is not possible to stretch the analysis farther than the headline topics and models featured on the magazine’s covers.

VOGUE ARRIVES IN JAPAN

As one of the oldest women’s fashion magazines today, Vogue—a brand of media company Condé Nast—is part of the global media and has by today 19 international editions from Ukraine to Taiwan and a gross international readership of 12.5 million.[2] Founded in 1892, Vogue was first exported to the United Kingdom in 1916, followed by a move to France in 1921.[3] As such, the magazine speaks to an urban and global audience, attributing the foundation of its “leadership and authority” in its “unique role as a cultural barometer for [this] audience.” By own definition, “Vogue places fashion in the context of culture and the world we live in—how we dress, live and socialize; what we eat, listen to and watch; who leads and inspires us. Vogue immerses itself in fashion, always leading readers to what will happen next. Thought-provoking, relevant and always influential, Vogue defines the culture of fashion.”[4] While speaking to the global cosmopolitan reader, each individual international edition adjusts to the different local cultures.

Its arrival on the Japanese magazine market was initiated through a joint venture agreement between Condé Nast and the Japanese financial newspaper Nikkei (short for Nihon Keizai Shinbun) which leaded to establishing the Nikkei Condé Nast Company and publishing Japanese Vogue’s launch issue in September 1999. (See “Image 01”) Vogue Japan, however, was not the first local edition in Asia, as Moeran shows: “Condé Nast made its first venture into the Asian market in 1996, when it launched Korean and Taiwanese editions virtually simultaneously. […] The reason for Condé Nast’s late arrival in Japan are various, and not entirely clear.” One of the obstacles was the extreme dynamic of the Japanese magazine market that, according to the author, is “overclassified, overcrowded, and thus extremely difficult to sustain a new title in successfully.” [5] However, Vogue Japan and present Editor-In-Chief Watanabe Mitsuko[6] have been successful and celebrated the 200th issue in April 2016 (See “Image 02”) with a current readership of 310,785[7], which acknowledges the international and elegant appearance of the Japanese Vogue and associates the magazine with the following image categories: “stylish, classy, good sense, jōhin (elegance), and—equally ranked—modern, international, and leading edge.”[8]

Image 02: April issue 2016 under the main headline “Retro Flash!“ presenting the 200th issue of Vogue Japan. |

Image 03: Singer Katie Perry featured on the September issue 2015 cover of Vogue Japan. |

WHY A WOMEN’S FASHION MAGAZINE?

With its understanding and branding as a lifestyle and fashion magazine for the cosmopolite, Vogue is visible on the magazine racks around the world and known by the urban consumer. The analysis of representation and content of global media helps in understanding what kind of cultural values, ideas of beauty and notions of identity are prevalent in local cultures. The local editions of such media constitute a field, where these identities and notions of one’s “self” and the “other” are constantly created and re-created.

As Moeran argues, “[w]omen’s fashion magazines are both cultural products and commodities. As cultural products, they circulate in a cultural economy of collective meanings, providing recipes, patterns, narratives, and models of and/or for the reader’s self. As commodities, they are products of the print industry and crucial sites for the advertising and sale of commodities (particularly those related to fashion, cosmetics, fragrances, and personal care).” Therefore, the negotiation between the individual relationships of the magazine with its readers and advertisers in the process from production to reception, transform the magazine into more than a cultural product or commodity— it becomes a cultural production.[9] In another article, he elaborates that “[w]omen’s magazines distinguish and define their target/client group by means of titles, covers, subject matter and advertisements—all of which help define women as biologically distinctive.”[10] Women’s magazines additionally help the reader to define the “self” through the means of aesthetics. As Clammer puts it, “[c]oncern with the body in society then necessarily raises philosophical and psychological questions—the issue of selfhood.”[11] In a further step, through distinguishing the Japanese consumer from the “other”—the Caucasian cover model—a magazine like Vogue Japan can play a role in the process of self-identification of the Japanese reader, or in Creighton’s words, it can “give meaning to Japanese identity.”[12]

SELF-IDENTIFICATION AND THE ROLE OF THE “OTHER” IN JAPAN

In her article on how Japanese department stores domesticate foreign produce, Millie Creighton illustrates how humans use categorical contrasts and juxtaposing polarities to define reality and “impose order on a potentially chaotic universe.” The tendency to structure everyday experiences is also prevalent in Japanese society, with a special emphasis on the categorical contrast between “Japanese” and the “other.” Miller asserts, that “by exaggerating the difference between Japanese things and non-Japanese things, Japanese customs and foreign ones, and ultimately, ‘ware ware Nihonjin’ (We Japanese) and ‘yosomono’ (outsiders, literally outside things)[, …] Japanese culture and national identity are affirmed.”[13] The representation of beauty through the sight of a Caucasian model on the cover of Vogue Japan falls into the same category and can arouse the reader’s interest through the display of difference. As Hall illustrates, when the notion of difference is used in a representation, it triggers and mobilizes deeply located emotions and mindsets.[14]

Stuart Hall further stresses the changing nature of identity creation through various different, intertwining, and also antagonistic discourses and practices. According to the author, identities are constructed with the notion difference at their base.[15] In order to appeal to the Japanese reader, the usage of disparities in the case of beauty representation on the covers of the Japanese Vogue has to be perceived in a positive sense. As such, it helps creating the production of meaning and social identity.[16] Hall claims that identities are constituted within representations, making them always a part of a constructed fantasy through the means of imagination.[17] Thus, similar to the role of ads in Japanese society, representations of beauty in media can be experienced as a “fantasy excursion” by the audience.

Vogue Japan as a “fantasy excursion”

Due to the way advertising imagery is established in Japan, the sight of Caucasian foreigners is prevalent.[18] Similar to other kinds of advertising, non-Japanese models on a fashion magazine cover are part of a visual imagery that presents these foreigners as “misemono, ‘spectacles’ or ‘things to look at’. In this sense, “[i]mages of foreigners are fantasy depictions, attention-getters, flights of fancy, which help construct Japanese identity by portraying what Japanese are not, and thus perpetuate a discourse of otherness.”[19] Showing non-Japanese models on the cover of a local edition of a magazine catches the eye of the Japanese passerby, aiming at attracting readers and selling issues. As already mentioned by Hall, this kind of representation is embedded in the construction of self-identity through “locating or imagining a contrasting other to highlight the distinguishing characteristics believed to define the self.” Furthermore, “[t]he prevalence of both foreign places and foreign faces in Japanese advertising functions to delimit Japanese identity by visual quotations of what Japan and Japanese are not.”[20] In interviewing different section heads of advertising companies, Creighton has found out about “[t]he sentiment that foreigners are aptly used to further [the] goal of creating fantasy moods”[21] and the depiction of gaijin, especially of Caucasian appearance, “fit into Japanese advertising images of ‘fantasy excursions’.”[22]

The same argument can be applied for the advertising function of the Vogue Japan covers. In this case, the foreign models furthermore play “a role as bearers of innovation, style, and value,” an example for the occidentalism of Japanese society, that, as Creighton illustrates, “arose in response to specific historical, political, and economic processes. As Western—and in the case of twentieth-century Japan, more specifically American—influence dominated the international scene, American material and popular culture began to permeate Japanese society. Gaijin became not all or any foreigners, but an essentialized projection of white Westerners. Japanese occidentalism exoticized gaijin, enhancing the appeal of advertisements that imaged or even referred to these strange but attractive alien beings. In ways parallel to Western orientalism, Japanese occidentalism also involved a sexual projection of the other, particularly the allure of the occidental woman.“[23]

In the following chapter I intend to show through a cover analysis how the first impression of the Japanese Vogue is not only that of a cosmopolitan “Western” magazine, but also incorporates a sense of Japanese occidentalism. In a second step, the content of the covers’ headlines reveals how the magazine is customized for the Japanese audience and thus balances the appeal of being “Western” and “Japanese” at the same time.

COVER ANALYSIS OF VOGUE JAPAN (2010—2015)

Image 04: International models and celebrities, such as musician Kanye West and designer Riccardo Tisci featured on the cover of the August issue 2015, underlining the overall theme of the issue “Fashion Gang.”

For the cover analysis I went through the monthly issues of the Japanese edition of Vogue, beginning with the January issue 2010 and ending with the December issue 2015, not including special issues like Wedding editions. Altogether, the 72 covers displayed 112 faces, of which 3 belonged celebrities—like singer Katie Perry. (See “Image 03”) Furthermore, designer Riccardo Tisci and musician Kanye West as the only two men on the covers in the 5 year span were featured both on the August issue 2015 besides actress Jessica Chastain and five international models. (See “Image 04”) Between 2010 and 2015 six of the 107 models were Japanese and only two more were non-Japanese Asian.

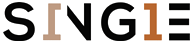

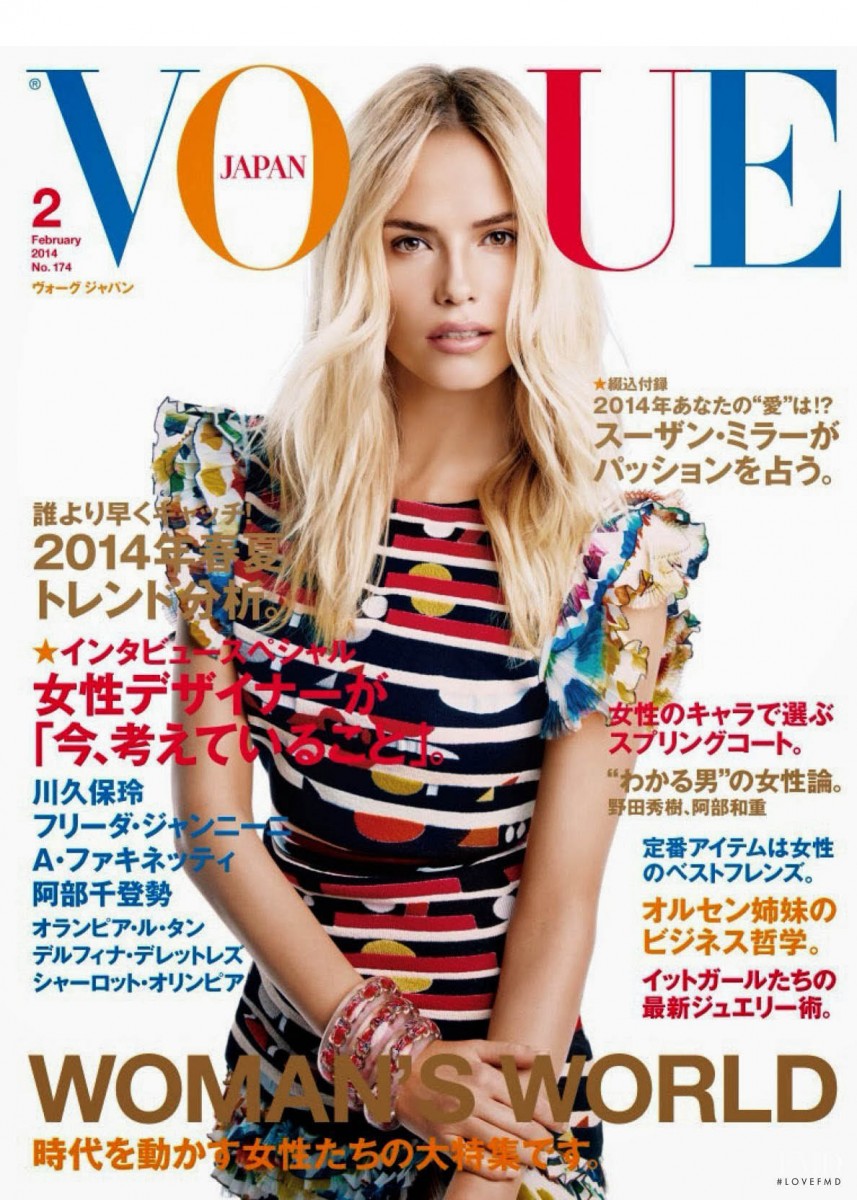

In addition to this prevalence of Western beauty representation the main headline of each issue is written in English and dictates the monthly theme of the magazine, such as “Boy Meets Girl” or “Retro Flash!” (See “Image 02”). Except for few other English headlines, announcing a series like “Women of the Year” or “Fashion’s Night Out”, the majority of printed words is kept in Japanese. For a reader not fluent or even familiar with the usage and existence of different Japanese scripts, the headlines might indicate a strong sense of “exoticism”. However, the headlines of Vogue Japan’s covers are predominantly using English words written in katakana and are as such immediately recognizable as non-Japanese words. As Tsunoda points out, “[t]he ubiquitousness of English words in Japanese books, magazines, and advertising copy stands out because foreign words (with the exception of Chinese and Korean) are customarily written in katakana, one of two Japanese syllabic scripts, whereas traditional Japanese words are written either in kanji, the Chinese ideographs, or in hiragana, the other syllabic script. A katakana symbol, consisting of a few simple, straight strokes and looking rather square, stands out saliently against a background of complex and dark-looking kanji characters and flowing, cursive hiragana squiggles.”[24] The different usage of katakana, kanji, and hiragana makes Japanese names that are written in kanji stand out next to English words written in katakana. More than that, the authors use different scripts for the words “Japan” and Japanese city names, like Tōkyō and Ōsaka, depending on the headline context. One can find the word “Japan”, but also its equivalent in katakana (ジャパン). The Japanese term Nihon/Nippon for “Japan“ can either be written in kanji (日本) or katakana (ニッポン). The play with different scripts makes the cover look dynamic, being “Western” and “Japanese” at the same time. The effort made by the editor seems important in the case of the Japanese Vogue’s cover. Moeran notes that “In Japan […] a very large number of readers buy a magazine on the basis of what they read each month while standing in a bookshop or convenience store (called “standing-reading,” or tachiyomi, in Japanese). This means that, even though it has a comparatively large subscription base, Japanese Vogue has to be structured in such a way that it will immediately appeal to a tachiyomi reader and persuade her to buy that month’s issue.”[25]

He furthermore stresses the importance of the cover to sell more issues: “The magazine cover is, of course, a means by which an Editor “anchors” the contents of an issue in order to make casual browsers at book and convenience stores stop to look through and, hopefully, buy her magazine. At the same time, cover headlines help relay the reader to other parts of the magazine, by going first to the Content pages and then to relevant sections that interest them.”[26]

The “other” as an eye-catcher

Image 05: Natasha Poly as cover model for the February issue 2015 was also the cover model for four further issues between 2010 and 2015.

Between 2010 and 2015 a total of 107 faces of international non-Asian models adorned the covers of Japanese Vogue’s monthly issues. The choice of models gives the magazine an overall youthful look, reflected in the young models that were most often shot for the cover: Karlie Kloss, Daria Strokous and Natasha Poly (See “Image 05”). Only 1.9% of the cover faces, namely six shots by five different models, were Japanese, of whom Okamoto Tao (See “Image 06”) was featured twice.

Image 06: Japanese model Okamoto Tao presents the androgyny “Boy Meets Girl” theme of the November issue 2009.

The tendency here is to represent more fashion and focus less on portraits, which is underlined by Moeran’s content analysis and the information he gained from magazine readers: “[V]irtually without exception, the women I talked to emphasized the importance of quality in the photographs they saw in their magazines. It was image that attracted their attention, and their fascination with images meant that—so far as the magazine readership was concerned—it did not matter if the clothes shown in the fashion pages of a title like Vogue were practical or not. What was paramount was that photographs should be striking and beautiful […].” Furthermore, the “readers generally agreed that Caucasian models made the clothes they wore look good (because they were tall and slender).” However, Moeran adds that “at a practical level, Japanese fashion titles, which made use of Japanese—or at least Asian—models, were seen to be more appropriate vehicles for advertising and consumption than foreign titles like Japanese Vogue.”[27] The eye-catching element of Caucasian models ends at a practical level. Here, the cover headlines and the presented content come in to make an issue more interesting for the local customers.

Selling to the locals through the covers’ headlines

The analysis of headlines from 72 different issues reveals recurrent topics and series customized for the Japanese audience. This may help in explaining the success of Japanese Vogue in their relationship with the readers and supports Moeran’s assumption that “[i]nternational editions of women’s magazines probably need to adapt to all sorts of different needs and expectations of different local readers by, for example, including discussions of local celebrities, local fashion reportages and models, and local of regional in Asia Japanese products, as well as those originating in Europe or the United States.”[28]

In fact, only twelve of the 72 monthly issues have no specific headline tailored for the Japanese audience. In the other 60 an average of two headlines address the local reader through series like “Women of the Year” featuring Japanese actresses, writer, and other celebrities, or a feature for travel in Japan and such. Several issues featured highly local content, like interviews with two female Japanese politicians in the November and December issues 2010 or specials about locally and internationally famous Japanese celebrities like author Murakami Haruki (04/2011) or actor Kitano Takeshi (09/2010). Further interviews that are interesting for the Japanese audience include Japanese architects, artists or musicians—like the J-Pop band EXILE—and popular successful figure skater Asada Mao and Takahashi Daisuke, which are also announced on the cover next to fashion topics. The Japanese Vogue advertises her issues also with international celebrities like singer Lady Gaga, and actresses like Angeline Jolie, but the high popularity of South Korean Pop music bands and TV Dramas leads to their constant featuring in the magazine. Interviews with popular South Korean actors in were announced nine times on the magazine’s covers. At the same time, six different Korean music groups were featured in Vogue Japan—the bands 2PM, BIGBANG and TVXQ appeared each on at least three different covers in the five-year-span. Japanese models, even though rarely seen on the covers themselves, made the topic of a headline eleven times.

Using locally popular celebrities and Japanese fashion authorities a part of the magazine’s content, the editor of Japanese Vogue has customized the local issue in a way that sells to the Japanese audience while making the fashion features internationally understandable to stabilize the magazine’s relationships to the advertisers and the fashion village.

CONCLUSION

The cover analysis of 72 monthly issues of the Japanese Vogue and the utilization of findings by Brian Moeran, Millie Creighton and others, shows how—despite its first impression of being “Western”—the women’s fashion magazine Vogue Japan successes in selling to their local audience by customizing the topic headlines and featuring foreign cover models as eye-catcher to “anchor” the reader’s attention. Choosing primarily Caucasian models for their cover shoots helps catching the readers’ attention by using the visual difference between the reader and the model. One reason, why this representation catches attention is rooted in Japanese occidentalism in which gaijin are among other things seen as misemono—or ‘things to look at’—and bearers of innovation and style. On a deeper level, distinguishing the Japanese “self” from the “other” on the magazine’s cover triggers the Japanese reader’s self-identification and adds the means of a “fantasy excursion” to the consuming process.

A deeper content analysis, as already done by Brian Moeran, reveals the additional magazine’s “reader-friendliness” for the Japanese target group. However, as I hope I could show, the analysis of the magazine’s cover already displays the balance between “Western” and “Japanese” that is achieved through different measures in order to cater for the different groups connected to Vogue Japan: its urban readers, the advertisers and the international fashion village.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Clammer, John R. Contemporary Urban Japan: A Sociology of Consumption, Studies in Urban and Social Change. Oxford, UK ; Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1997.

- “Condé Nast International – Brand.” Accessed March 31, 2016, http://www.condenastinternational.com/brand/?b=vogue#vogue.

- “Condé Nast International – Brand – Vogue.” Accessed March 31, 2016, http://www.condenastinternational.com/country/japan/vogue.

- “Condé Nast – Vogue.” Accessed March 31, 2016. http://www.condenast.com/brands/vogue.

- Creighton, Millie R. “Imaging the Other in Japanese Advertising Campaigns,” in Occidentalism. Images of the West, ed. by James G. Carrier. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995. 135–60.

- Creighton, Millie R. “Maintaining Cultural Boundaries in Retailing: How Japanese Department Stores Domesticate ‘Things Foreign,’” Modern Asian Studies 25, no. 4 (1991): 675–709.

- Hall, Stuart, et al., Ideologie, Identität, Repräsentation, 4. Aufl, Ausgewählte Schriften, Stuart Hall ; 4. Hamburg: Argument-Verlag, 2004.

- Moeran, Brian. “Elegance and Substance Travel East: Vogue Nippon,” Fashion Theory, vol. 10, issue 1–2 (2006): 225–258.

- Moeran, Brian. “On Entering the World of Women’s Magazines: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Elle and Marie Claire,” in Marketplace Anthropology, ed. by Nasreen Taher and Swapna Gopalan. Hyderabad: Icfai University Press, 2006. 187–209.

- Tsunoda, Waka. “The Influx of English in Japanese Language and Literature.” World Literature Today 62, no. 3 (1988): 425-430.

IMAGES

- “FMD – Vogue Japan > Covers.” Accessed March 31, 2016, http://www.fashionmodeldirectory.com/magazines/vogue-japan/covers.

NOTES

brand/?b=vogue#vogue