A visual essay by Amy Clare

Introduction & Definition of Masculinity:

Masculinity is not something that is simply possessed by all men in all contexts (Horrocks 1994). Understanding masculinity is difficult as it varies depending on culture, time, generation and even individual belief and perception. Since masculinity is fluid and constantly changing it is difficult to come up with a set definition. However, for the sake of this paper, masculinity is to be understood as the set of qualities accepted by a majority of the population in relation to being male (Yang 2010, 10). The focus in particular is the set of qualities related to being a Chinese male in the 21st century and how these qualities have been altered or challenged by new socioeconomic developments.

In China, historically the dominant sex has always been male. They were the sole breadwinners and individuals who participated in the public sphere. However, with China’s economic reform starting in 1978, women began to enter the labour force (Chen et al. 1992, 202). Women in China are now gaining more freedom and power than ever before. It is often argued that masculinity is fragile. It must be attained by men and proven through formal or informal rights of passage (Badinter 1995, 9). The fragility of masculinity is shown when in direct opposition to femininity, as it can be lessened or weakened (Heinrich and Martin 2006, 147). Has the newfound power and autonomy of women begun to destabilize realms that were previously male dominated (Heinrich and Martin 2006, 147)? It can be proven that the introduction of women into the business world has affected masculinity in China, and gender dynamics.

This paper briefly explores the previous history of Chinese masculinity, how it has changed and is understood by professionals nowadays and the sociocultural impacts modern women have had on it. The particular focus is how businessmen and businesswomen understand masculinity and how this understanding is affecting social aspects in China today. Please note masculinity is being discussed solely in relation to white-collar professionals in urban centers in China, not the entire population.

History of Chinese Masculinity to Now:

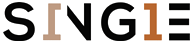

In order to understand what changes are occurring in Chinese masculinity today one must first look to the past. Kam Louie explains the dyad of traditional Chinese masculinity: wen and wu (Louie 2000, 1065). These two archetypes were understood as the following: Wen masculinity emphasizes culture and knowledge based power, symbolized by Confucius and gentlemanly scholars or officials and Wu a masculinity focused on physical prowess through martial and physical strength and skill (Heinrich and Martin, 2006:224). Neither the scholar nor warrior were understood as less masculine than the other and it was said that “there is no man who does not have something of the way of wen and wu in him” (Yu 1979, 156). However, sometimes there was the notion that those who were more wen and worked in a scholarly way ruled over those who worked physically, or had more wu associated with their masculinity (Louie 2000, 165). This would support the idea that white-collar professionals were more masculine than their blue-collar counterparts.

Fig. 1: Refined Scholars

Traditionally these understandings were strictly related to men and could not be applied to women (Louie 2000, 1065). Women were only considered in the wen/wu dynamic as objects men could exercise self-control over to add to their image of masculinity (Louise 2015, 2). At the opposite end of the spectrum there was the belief that “sadistic violence against women serve[d] as a potent sign of masculine prowess” (Louie 1999, 845). The relationship between women and masculinity was either avoidance to show men’s self-control or abuse to assert machismo dominance.

Fig. 2: Warrior Masculinity

It was until the 1980s that Chinese masculinity maintained “hegemonic aspects in the sense that men had dominance over women and certain classes of men were privileged over other groups” (Louie 2015, 1). At the turn of the 20th century this changed as women began to participate in the public sphere and thus could have the wen/wu dyad applied to them as they took on scholarly or physical roles (Louie 2015, 4). As women entered the labour force the masculinity crisis within China’s class structure began (Yang 2010, 551). In recent decades there has been the idea that femininity is diminishing masculinity (Yang 2010, 100). The influx of women in the economic realm who are attaining positions of power has “created the fear that men will fall behind in the competition for success in life” (Louie 2015, 4). The wen/wu dyad that upheld white-collar professionals as more masculine is still apparent today, however the notion has been altered as women now exist in the business world as well.

Current Status of Men & Women in China:

To understand the context masculinity is constructed within it is paramount to examine the current status of men and women in China. China’s society is now heavily consumerist (Lee and Song 2010, 159). As more individuals gain waged positions, their ability to participate as consumers increases. China’s economic reform and post-Mao ideology advocated consumerism as a link to modernity (Zheng 2006, 163). Men and women in urban centers in China especially desired this advancement to modernity as held the promise of a better life. Thus the desire for modernity through participation in a consumerist society propelled more men and women to enter the business world.

The increase of women in prestigious professional positions is a crucial socioeconomic phenomenon of the 21st century (Griffiths 2014, xii). Evidently the economic activity rates amongst Chinese women between the ages of 25-29 in 1980 were 87% and in 2000 that number leaped to 92% (Zhang et al. 2008, 1533). It appears that women are more active in the economy than ever before. This change in demographics has inevitably impacted the professional realm and their counterparts, businessmen.

Masculine dominance is further challenged by the social liberalization of female sexuality in China. Since the 1990s “urban Chinese hold more liberal and tolerant attitudes toward sex” (Attané et al. 1992, 19). Women are gaining more autonomy and independence from having their own jobs and have thus become less dependent on nuclear relationships with men. Combined with the population imbalance caused by the one child policy, women have more choice than ever for a partner, if they decide to have one at all.

Business Men:

As there are a variety of contexts masculinity can be examined in, this specific paper will focus on the modern Chinese businessman. In Zurndorfer’s article it is proposed that male perfection is the confident businessman (6, 2015). Related to the traditional wen and wu masculinities, this embodies more of a wen ideal: a scholar or person who is working with their mind rather than body. From the 1990s onwards, the well-groomed, confident corporate white-collar businessman became the perceived essence of masculinity in China with his high income and material success (Zurndorfer 11, 2015). This is an image that even transcends China’s borders. In America, Chinese entrepreneurs are “obsessed with displays of conspicuous wealth and brand names” (Louie 2012, 931). The masculinity of the businessman is linked to success and an ability to participate in a consumerist society where material goods prove maleness.

Fig. 3, 4, 5: Examples of the ideal businessman in Chinese magazines

In men’s magazines it is commonplace to see razors, or watches that belong to the masculine businessman ideal and beside these objects provocative photos of women (Lee and Song 2010, 169). The juxtaposition of these images in magazines “suggests that upward class identification may be achieved through the consumption of women” (Lee and Song 2010, 169). The businessman’s masculinity is enacted via sex, and sexual undertones, which enhance his image and make him look like more of a man. However this does not occur with all women, especially not those who are in a similar professional standing.

Masculinity achieved through sex can be regularly witnessed at karaoke bars where colleagues will go as a group outing. The success of projecting a masculine image depends on participation in extramarital affairs as a ritualized leisure amongst work colleagues. There is a need to show a rational cool masculinity through conquering emotions of women hostesses (Zheng 2006, 162). Often this treatment of women is not solely for pleasure but is linked to a businessman’s ability to advance professionally. Opportunities for upward mobility within the elite circles of Chinese business and government depend on these group outings and perceived attitudes towards women (Zheng 2006, 162). Not only does this treatment foster opportunities but it also creates unit cohesion between colleagues strengthening and solidifying their positions (Zheng 2006, 167). The enacted subordination of women as a means of increasing one’s potential to be promoted coincides with the epitome of masculinity.

Fig. 6: What hostesses experience at karaoke bars

Fig. 7: Interior of a karaoke lounge where businessmen congregate

Fig. 8: Hostesses and businessmen interactions

Even individuals who do not wish to act this way towards women may be coerced into it. A bank clerk, Liang, in his early 30s explained how peer pressure is often felt by men to act this way with hostesses. Liang states, “You just have to patronize hostesses. You’ve got to try it a few times. It’s part of growing up and self-actualization. Otherwise, when other men are talking about it, you would look like a fool who never enter society in an experienced fashion. Nobody would respect you if you were like that. So you have to have this experience to gain others’ recognition and respect.” (Zheng 2006, 166). Men will see colleagues performing this aspect of masculinity and feel that they have proven their manliness, and thus want to promote them or continue to work with them since they are “real men”. If men do not participate, their impotence is seen as inadequate and leads to intense feelings of emasculation (Zheng 2006, 164). It is explicitly mentioned that men use their wealth to seduce hostesses, as it is commonly agreed that no matter how beautiful a hostess is she cannot refuse an ugly but wealthy man: class equality is achieved through the consumption of sex (Zheng 2006, 164). Alternatively, ‘“high quality beautiful women are rewards for successful men and indicators of status” (Lee and Song 2010, 169). Those who do not wish to act this way towards women are emasculated, which is the same for those who cannot afford to participate.

The masculinity of the businessman is performed through the consumption of material goods and women’s bodies. It is through these two major outlets that they feel they are fulfilling their imagined perceptions of what it means to be a truly successful man.

Fig. 9: Images of a KTV karaoke bar

Businesswomen:

As a direct opposite to the businessman, the businesswoman has emerged. There are more women employed in high positions than ever before in China. This trend is continuing as more women attain professional educations and enter into waged positions. Although it would be assumed there is companionship between men and women in business, there is strong disdain for businesswomen. Businessmen will attack their looks and personalities as they are frequently accused of “lacking feminine charms and virtues” (Zurndorfer 13, 2015).

Fig. 10: Zhang Xin

Fig. 11: Dong Mingzhu

Fig. 12: Wang Xiaojun

As more women are penetrating into what were once male dominated disciplines, businesswomen are challenging masculinity. This is seen by men as opposition and often invokes vengeful and derogatory retaliation. For instance women who achieve equal professional footing as their husband have negative connotations associated with them. Mentioned more than once are feelings of inadequacy, which are exacerbated by a wife’s employment when men lose their jobs (Yang 2010, 557). It has also been demonstrated that marriages falter when a wife is promoted and earns more than her husband (Zurndorfer 13, 2015). When men do not see themselves as attaining the dominant position in a relationship or marriage, the perceived power imbalance causes problems.

Changes from Traditional Roles:

Previously masculinity in the wen/wu dyad was not significantly threatened by femininity as it was only related to males. Now that women are taking over more traditionally masculine roles and professions, masculinity is changing. Rather than avoidance of women or abuse of women to prove manliness as previously shown in the wen/wu dyad, men must now seduce women. The businessman’s “masculinity is equated with wealth and power, and women and sex are proof of men’s success” (Lee and Song 2010, 176). This causes issues when men cannot entice women or feel they are emasculated.

Masculinity is fragile and the presence of businesswomen and their femininity is altering it, thus men are trying to subordinate women in alternative means. This is seen when men buy into masculinity through consumerism and treat women who are in lesser positions of power (i.e. hostesses) as objects. If the women are peers of a professional level then subordination and undermining them is done through slander. This reassertion of dominance over women is done through either extreme feminization of them, reducing them to sexual objects, or exclusion within the professional realm (Zheng 2006, 168).

Although women in a professional setting are regularly slandered by their male counterparts their ability to compete for money, power, and respect has ultimately caused a paradigm shift with inter-gender roles and relationships. One aspect of cultural production that has been affected by the influx of women participating in the consumerist society of China is that of men’s magazines. It is not a reversal of the male gaze per se, but the introduction of a female gaze as women are starting to read men’s magazines as a means of learning more about men (Lee and Song 2010, 170). These magazines tend to objectify the male body now because that is what their female consumers desire and will ultimately increase sales and readership. This shift to objectifying men as a sexual fetish shows the change in gender dynamics since now there is a “contradiction between the vulnerable passivity arguably implicit in the state of being-looked-at and the dominance and control which patriarchal order expects its male subjects to exhibit” (Kirkham and Thumim 1993, 12). Chinese men have become a commodity for female consumption through these magazines (Baranovich 2003, 143). This is a drastic shift compared to previous eras, which only came about from the amount of women in business positions who have the capital and agency to influence change.

The New Dating World:

The new professional world and it’s altered inter-gender dynamics inevitably are impacting how these men and women date. The masculinity of businessmen and associated values may advocate the idea they are not traditional, however this is not entirely true. Many men maintain traditional views that they should be the sole breadwinner and take care of their wife and children. It has been proven modern Chinese men feel “being the breadwinner is the sole purpose of being a man” (Yang 2010, 109). One PhD student in his 30s explained “what I have been doing all my life is to prepare myself to build a family and provide for my family” solidifying the idea that some men are still working towards the idea of having families and taking care of them (Yang 2010, 75). Men who hold this ideal to marry, maintain previous beliefs that the women should not be equal economically so that they can be the sole breadwinner.

Since women are a lot more economically advanced than previous years, this is causing men to work until their mid to late 30s prior to seeking marriage since they feel they need to be substantially economically advanced (Jones et al. 2012, 737). Men want to be substantially more successful than their female counterparts when entering a marriage or they feel they are not fulfilling their masculinity. One man explained how this gender anxiety leads to “a terror of being construed as feminine, feminized, of no longer being properly a man, of being a ‘failed’ man” (Yang 2010, 557). Chinese men are exhibiting anxiety over losing prestige to a “weaker sex” and not being the predominant breadwinner in the family, or in a relationship (Lee and Song 2010, 143).

Businesswomen are looking for someone with equal income and material conditions (Women of China). Women express a desire to find a partner of equal or greater socioeconomic standing due to the fact they “don’t want their partners to feel too much pressure and eventually lose their masculinity” (Jones et al. 2012, 744). It is acknowledged and known that men feel emasculated by successful businesswomen. Unfortunately it seems young, professional Chinese women are in a catch-22: if they earn too much their marriage opportunities diminish as men do not want to marry wealthier wives and if they marry a more successful man they are accused of using feminine charm to seduce their way to a higher social standing (Zurndorfer 9, 2015). This is the current situation that businesswomen in China are facing today. This is causing marriage and dating to occur later and later, if at all.

Even if marriage is a goal for some men and being the breadwinner is the epitome of masculinity for them, there is still a discrepancy due to “marrying up/down” (Kohlbacker and Shi 2016). Ma Chunhua a gender specialist at CASS explains that there’s a “scarcity of men at top end of social pyramid and of women at the bottom, driven by economic changes”: “The A men marry the B women, the B men marry the C women, the C men marry the D women. The only groups left are the A women and the D men, and the D men can bring in the E women, the mail-order brides” (Clover 2016). This is the new reality in the dating world of business professionals and how it trickles down to all levels of society.

Key to this idea of “marrying up/down” is consumerism. As women become consumers and take over more sociopolitical and economic power in China, their desires are changing. They are changing how the sexual desirability of men is perceived (Louie 2012, 939). On the website Women of China it was noted in a social media poll that “Chinese men are not enough for Chinese women 33% of females supported it and 6% of men” (Women of China 2016). Successful women do not want to “marry down” to less successful men because they know that it will cause issues with emasculation.

Fig. 13: China’s gender imbalance

Combining the gender imbalance in China with a woman’s autonomy in relationship formation has given her a position of power and choice that women did not previously have. This result will continue to persist as it is predicted that the gender imbalance in China will worsen (Kohlbacker and Shi 2016). One professor at Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics suggested polyamory as the solution to this imbalance: as a utilitarian argument that women should be allowed to marry more than one man (Keating 2016). This shows clearly that women have challenged the traditional role of men in relationship formation and now hold autonomy at such a level that they possess the selection and decision making roles over men.

Ultimately it seems that modern Chinese masculinity is chaotic and contradictory (Yang 2010, 105). There is no simple understanding of Chinese masculinity in the modern era. It is clear that there has been a shift away from the wen/wu dyad though, albeit the wen ideal of the scholar and gentleman has taken precedence. Perhaps it is due to the new globalized China and the economic revival, but the masculinity of the successful businessman appears to be the new ideal. This fragile masculinity however can be, and often is, affected by businesswomen. Thus businessmen take to karaoke bars to exert and reconfirm their masculinity over other females who are not of equal economic and professional standings. As more women continue to join the professional world it will be interesting to see how future marriage and dating patterns change and develop.

Works Cited

- Attané, Isabelle, Zhang Qunlin, Li Shuzhuo, and Yang Xueyan. “Male Singlehood, Poverty and Sexuality in Rural China: An Exploratory Survey.” Population-E 65 (2010): 679-694. Accessed January 17, 2016. doi: 10.2307/41337098

- Badinter, Elisabeth. XY On Masculine Identity. Translated by Lydia Davis. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

- Baranovich, Nimrod. China’s New Voices: Popular Music, Ethnicity, Gender and Politics 1978-1997. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

- Chen, Kang, Gary H. Jefferson and Inderjit Singh. 1992. “Lessons From China’s Economic Reform.” Journal of Comparative Economics 16: 201-225.

- Clover, Charles for Gulf News. “The Mystery of China’s Missing Brides.” Accessed January 17, 2016. http://gulfnews.com/culture/people/the-mystery-of-china-s-missing-brides-1.1653575

- Griffiths, Rudyard, eds. Are Men Obsolete? The Munk Debate on Gender – Rosin and Dowd Vs. Moran and Paglia. Toronto: Aurea Foundation, 2014.

- Horrocks, R. Masculinity In Crisis: Myths, Fantasies and Realities. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

- Heinrich, Larissa and Fran Martin. Embodied Modernities: Corporeality, Representation, and Chinese Cultures. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006.

- Jones, Gavin W., Zhang Yanxia and Pamela Chia Pei Zhi. 2012. “Understanding High Levels of Singlehood in Singapore.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 43 (5): 731-750.

- Keating, Joshua for Slate. “Economic Says Polyamory Can Solve China’s Gender Imbalance. Chinese Internet Explodes.” Accessed January 17, 2016. http://www.slate.com/blogs/xx_factor/2015/10/26/economist_says_china_s_gender_imbalance_can_be_solved_by_polyamory_chinese.html

- Kirkham, Pat and Janet Thumim (eds). You Tarzan: Masculinity, Movies and Men. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

- Kohlbacker, Florian and Lin Shi for China Economic Review. “If You Aren’t the One: China’s Dating Site Market Suffers From Some Chronic Trust Issues.” Accessed January 17, 2016. http://www.chinaeconomicreview.com/op-ed-chinas-dating-site-market-suffers-some-chronic-trust-issues

- Lee, Tracy K. and Geng Song. 2010. “Consumption, Class Formation and Sexuality: Reading Men’s Lifestyle Magazines in China.” The China Journal 64: 159-177.

- Louie, Kam. 1999. “Sexuality, Masculinity and Politics in Chinese Culture: The Case of the ‘Sanguo’ Hero Guan Yu.” Modern Asian Studies 33 (4): 835-859.

- –––––––––––––. 2000. “Constructing Chinese Masculinity for the Modern World: with Particular Reference to Lao She’s The Two Mas.” The China Quarterly 164: 1062-1078.

- –––––––––––––. 2012. “Popular Culture and Masculinity Ideals in East Asia, with Special Reference to China.” The Journal of Asian Studies 71 (4): 929-943.

- –––––––––––––. Chinese Masculinities in a Globalizing World. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Women of China. “Interesting Facts about Chinese Relationships, Marriages: Reports.” Accessed January 17, 2016. http://www.womenofchina.cn/womenofchina/html1/survey/1601/675-1.htm

- Yang, Annie Yen Ning. “An Expedition Into The Uncharted Territory of Modern Chinese Men and Masculinities.” PhD diss., University of Missouri-Columbia, 2010.

- Yang, Jie. 2010. “The Crisis of Masculinity: Class, Gender, and Kindly Power in Post-Mao China.” American Ethnologist 37 (3): 550-562.

- Yu, Lun. Confucius: The Analects. Translated by D.C. Lau. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1979.

- Zhang, Yuping, Emily Hannum, and Meiyan Wang. 2008. “Gender-Based Employment and Income Differences in Urban China: Considering the Contributions of Marriage and Parenthood.” Social Forces, 86(4): 1529-1560.

- Zheng, Tiantian. 2006. “Male Clients’ Sex Consumption and Business Alliance in Urban China’s Sex Industry.” Journal of Contemporary China 15 (46): 161-182.

- Zurndorfer, Harriet. 2015. “Men, Women, Money, and Morality: The Development of China’s Sexual Economy.” Feminist Economics (2015): 1-23. Accessed December 8, 2015. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2015.1026834

Photo Sources: